Different Senses of ʿAql (Reason) in Early Islam

In the parlance of Islamic studies, the Arabic العقل is usually rendered “reason” or “intellect”. While these translations are not inaccurate, they are, however, restrictive, as well as being indifferent to the variegated senses in which ʿaql was used and understood by different groups and in different intellectual milieus of early Islam.

In what follows, I aim to present six different intellectual attitudes towards reason and the role of reason in early Islam. By early Islam I mean the first two or three centuries after the death of the Prophet Muḥammad in 632 AD. Like those before them, early Muslim authorities and intellectuals needed to come up with ways to understand the world around them, to make sense of the principles of faith, and to ask the all-important questions:

- How does one come to know—anything?

- What constitutes certainty?

- What is the most efficacious mode of thinking?

- Is it an epistemology grounded in scripture, reason, mysticism, or something else?

- And, lastly, is thinking a purely intellectual endeavour severed from human emotions, ethics, and community?

First, in the context of the Qurʾan. The terms ʿaqalah and yaʿqilu, as cognates of ʿaql, appear over fifty times in the Qurʾan. They are employed as conceptual equals to tafakkur (تفكر) and tadhakkur (تذكر). In the quranic discourse, the term ʿaql, and its conceptual cognates, reflects a plethora of interconnected concepts associated with meditative reflection of the divine and the remembering of godly bounties bestowed on humanity which is in turn closely tied to assent and submission to divine authority (as Amir-Moezzi argued in his Early Divine Guide).

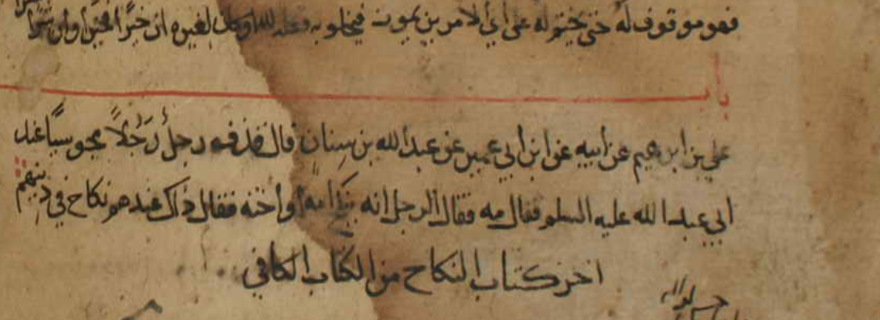

SECOND, in the context of traditional Shiʿism (before the fifth/eleventh century). The opening chapter of the ḥadīth compendium of al-Kāfī, by Muḥammad b. Yaʿqūb al-Kulāynī (d. 329/940), is devoted to ʿaql and jahl, aptly entitled Kitāb al-ʿaql wa-l-jahl(which contains 36 traditions). A careful reading shows that for early Shiʿi Muslims, arguably the first philosophically mindful community in Islam, the traditions cover four interrelated themes and concepts (addressed in detail in the Early Divine Guide).

In Theme One, ʿaql is understood as a cosmic morality that guides the faithful in his or her quest to overcome impiety and ignorance. In a tradition attributed to the sixth imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 148/765), ʿaql is said to consist of 75 traits (described as جنود), which include faith, justice, soft-headedness, knowledge, mercy, restraint, and munificence. Each trait (or jund) is contrasted with its opposite. For example, simple-mindedness is contrasted with comprehension; justice is the opposite of evil; knowledge is contrasted against ignorance; patience against impatience; pardon against revenge; and restraint is the opposite of anger. That is to say, rational is the person who pardons his enemy rather than plot revenge, who shows justice rather than oppress, and who acts in the spirit of goodness rather than evil.

In Theme Two, ʿaql is defined as an ethical and epistemological tool that helps the believer arrive at sound judgments and informed decisions. The ethical and epistemological dimension of ʿaql can be developed by studious education rooted in the teachings of the Prophet and the Ahl al-Bayt, his Progeny. The Ahl al-Bayt in Shiʿi Islam are the archetypal possessors of rationality, the paragons of reason, and the masters of analytical thinking. In a tradition recalled by the sixteenth century Shiʿi philosopher, Mulla Ṣadrā al-Shīrāzī, the first imam, ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, is described as the Aristotle of the Muslims, owing to his impeccable powers of intelligent speech, penetrating arguments, and analytical comprehension skills. In this regard, to possess ʿaql is to be like the Prophet Muḥammad and ʿAlī; it is a way of being human, in the sense of being caring and compassionate, of elevated character, pious, ardent in religious practice, and analytical and rational.

As for Theme Three, ʿaql is taken to be a metaphysical means to perceive and comprehend the divine. The traditions describe ʿaql as a type of interior vision (بصر) that brings the believer to recognise the “signs of God”. The believer comes to understand God and the realm of divinity through sacralised reason, that is, the type of reason that invites reflection of the signs of God around us, to find order, wisdom, and volition in the wonders of creation. The possessor of ʿaql is much like the modern-day astronomer: he or she observes the realms of heaven to find meaning behind the splendour and grandeur of creation, and, more significantly, to arrive at knowledge of the divine operation in all things celestial and earthly.

And finally, in Theme Four, ʿaql is described as a soteriological dimension that guarantees salvation, conceptually encapsulated by the famous ḥadīth of Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, who, responding to the question what is ʿaql? said, “it is that by which the Merciful is worshipped and through which Paradise is attained”.

العقل ما عبد به الرّحمن واکتسب به الجنان

THIRD, in the context of traditional Sunnism. Traditional Sunnism split into two camps over the concept of ʿaql, with one camp rejecting the traditions of ʿaql as of dubious attribution, while the other considered a number of these traditions as consisting of sound meaning. Two figures stand out as the salient representatives of the rejectionist camp: Ibn Ḥibbān al-Bustī (d. 354/965), the famous Shāfiʿī traditionist and evaluator of ḥadīth, and Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah (d. 751/1350).

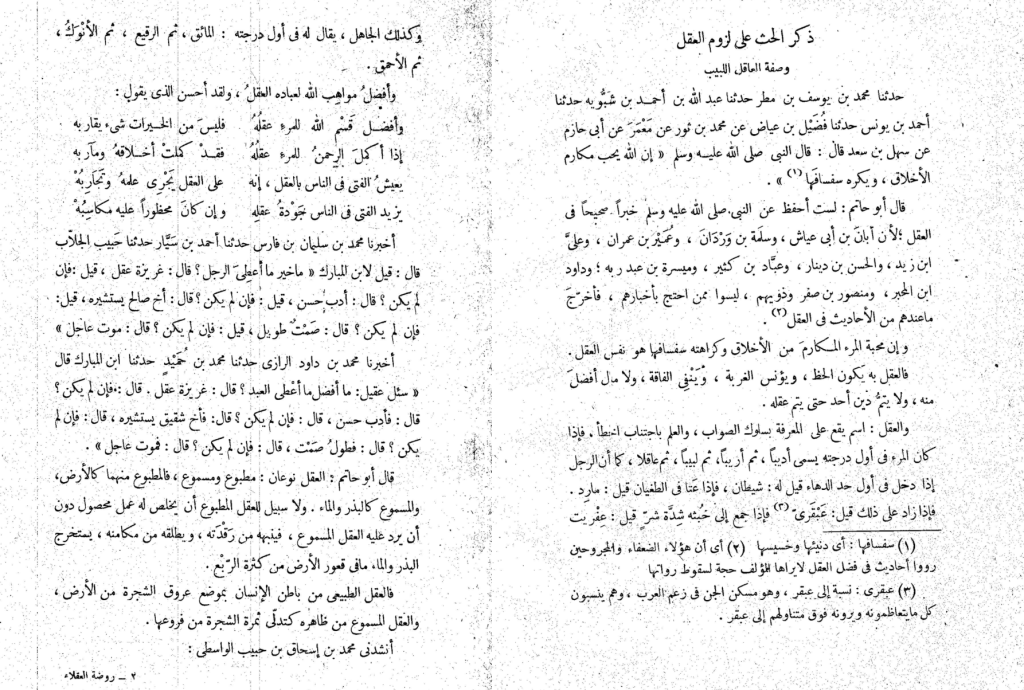

In his Rawḍat al-ʿuqalāʾ wa-nuzhat al-fuḍalāʾ, Ibn Ḥibbān writes critically of the purported ʿaql traditions attributed to the Prophet Muḥammad, dismissing them as unsound and lacking in veracity. The lack of scriptural provenance notwithstanding, Ibn Ḥibbān goes on to list the qualities of the one who possess ʿaql (the opposite of the ignorant, al-jāhil). He defines the essence of ʿaql as yearning to achieve refined ethical behaviour and to dispel ill-manners. To be a possessor of ʿaql is to behave righteously and to act with the high decorum of Islam.

Similarly, Ibn al-Qayyim, in his al-Manār al-munīf fī l-ṣaḥīḥ wa-l-ḍaʿīf, dismisses all the traditions about ʿaql as fabrications that have no basis in the sunnah. That is not to say, Ibn al-Qayyim and other medieval traditionists of the Sunni camp were anti-rational, if we defined ʿaql as rationality of some kind. On the contrary, Ibn al-Qayyim held on to the view that it is possible to approach ḥadīth criticism with some degree of rationality.

Representing the second camp in traditional Sunnism and adopting a less dismissive attitude than those before and after him, was Ibn Abī l-Dunyā (d. 281/894), the famed littérateur and tutor of several ʿAbbasid princes. In his Kitāb al-ʿaql wa-faḍluh, Ibn Abī l-Dunyā records 102 traditions about ʿaql. A few traditions recounted have Shiʿi isnāds, such as the tradition tracing back to the Kufan Shiʿi traditionist Abū Ḥamza al-Thumālī (d. 149/766). The traditions highlight the ethical dimension of ʿaql as well as its ability to caution against foolhardiness.

For the accommodationist camp among traditional Sunnis, ʿaql is a means to cultivate good ethical conduct and to avoid bad habitual traits. In other considerations, it is said that the possessor of ʿaql is elevated by God. In fact, the true worth of man lies in religion, their worth of humanity in reason, and true worth in lineage in good morals.

Hardly in conflict with religion, reason, according to Ibn Abī l-Dunyā, is a good measure of piety and spiritual commitment. The pious believer is once rational, ethical, and studiously observant of Islamic injunctions. The journey towards God, the Prophet Muḥammad is quoted by Ibn Abī l-Dunyā, finds direction towards its finality and ultimate achievement by the perfection of human reason. Reason is not simply a tool of intellection to make sense of the world around us. Nor is it an epistemological apparatus of cognitive inquiry and intellectual discovery. It is reaches beyond the theoretical and into the practical. Reason, we learn, teaches man to act justly, fairly, an in true communitarian spirit.

FOURTH, in the context of major kalām traditions, such as the Muʿtazili, Ashʿari, and rational Shiʿi. Starting with the Muʿtazilis, there was a broad agreement among their early and later proponents that ʿaql (used interchangeably with fikr, contemplative reflection) is an epistemological tool of discovery that precedes the probative authority of scripture (الفكر قبل ورود السمع).

For the Ashʿaris, ʿaql is that which leads to discovery of new knowledge after reflective and discursive thinking. The agent possessing ʿaql (العاقل) must distinguish between sound and distorted reflection (النظر). The former is where the conclusion follows necessarily from the premise, while the latter is its opposite. The primary objective of ʿaql is to arrive at the knowledge that the world was created in time, as explained by the renowned Ashʿari theologian Imām al-Ḥaramayn al-Juwaynī (d. 478/1085) in his Kitāb al-irshād.

The rational Shiʿi view of ʿaql is presented by al-Shaykh al-Mufīd (d. 412/1022) in his credal summary Awāʾil al-maqālāt, where he describes ʿaql as a tool of investigation and demonstration that must act in tandem with scripture—and not independently of it. For al-Mufīd, ʿaql is a tool that operates alongside scripture in order to arrive at new knowledge, such as knowledge of God, good and evil, and the necessity of following a divinely appointed guide.

FIFTH, in the context of early Arabic philosophy as exemplified in the peripatetic tradition. In his Risālah fī l-ʿaql (رسالة في العقل), the towering Arabic philosopher Abū Naṣr al-Fārābī (d. 338/950) assigns multiple senses to the intellect (al-ʿaql) following the division found in Aristotle’s De anima, where intellect has the sense of potential, actual, acquired, and active.

The potential intellect is that part of the soul disposed to abstract quiddities and forms. The active intellect, writes Fārābī, renders the thing that was potential intellect an actual intellect. The acquired intellect is the sense where all or most of intelligible thoughts are known to the agent. The last, namely the active intellect, is the cause of human thought. The active intellect relies on concepts to enable the human intellect to think by abstracting the forms that it emanated into matter.

SIXTH, in the context of Ismaʿili Shiʿism. The Neoplatonic Ismaʿili philosopher and theologian, Nāṣir-i Khusraw (d. 480/1088), in his little-studied Persian work Jāmiʿ al-ḥikmatayn, proffers a definition of ʿaql in line with the teachings of the Shiʿi imams (whom he calls ahl al-taʾyīd). We are told that ʿaql is a simple substance through which human beings form concepts of things. The ʿaql is the guardian of the rational soul and that which gives the soul its noble status and possibility of self-awareness. Knowledge, he says, is the activation of the intellect, and the intellect is bestowed to humans by God.

This, then, is a brief summary of the main senses in which the term ʿaql was employed and understood in the early centuries of Islam and among different groups, ranging from the traditionalists, theologians, philosophers, and in the text of the Qurʾan. To the best of my knowledge a dedicated monograph that studies and investigates the conceptualisations of ʿaql in early Islam is yet to materialise. There are however a few dedicated studies which deal with ʿaql in specific and restrictive contexts, such as the Arabic philosophical tradition of the peripatetics, but these studies fail to take into account doctrinal developments of the concept and the intra-religious debates surrounding the scope and purview of ʿaql after the move towards canonisation in the third/tenth century.