Hishām b. al-Ḥakam and Hellenism

A century ago, Carl Becker, in his work Islamstudien: Vom Werden und Wesen der islamischen Welt, observed that Islam builds upon and preserves Christian–Antique Hellenism, and that a time will come when one will learn to understand late Hellenism by looking back from the Islamic tradition.

Becker was right in many ways. The first two centuries of Islam remain vast, unexplored oceans brimming with insights into late Hellenism—preserved nowhere else but in those early Islamic periods. In class not so long ago, we spent three hours delving into the worldview and thought of Hishām b. al-Ḥakam, who lived in the middle decades of the 700s AD.

Hishām fascinates me; his knowledge of ancient traditions surpassed that of many in his generation. Initially a follower of Jahm ibn Ṣafwān, who died in 745, he later turned to Imāmī Shiʿism and became part of the circle around Imām Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, who passed in 765. What makes Hishām so intriguing is his familiarity with Hellenistic thought. Far from certain is our knowledge of whether early Muslim communities of Iraq encountered Hellenism before the translation of more formal canons from Greek.

It is quite likely—possible, even—that Hishām spent time in the circles of Syriac Christians in Iraq. One name in particular comes to mind: Abū Shākir al-Dayṣānī, named after the third-century AD figure Bardaiṣan. Was Hishām familiar with the ideas of al-Dayṣānī? The sources suggest as much.

Whoever Hishām’s sources were, he stands out as perhaps the earliest known theologian who furnishes a physical link between late Hellenism and early Islam.

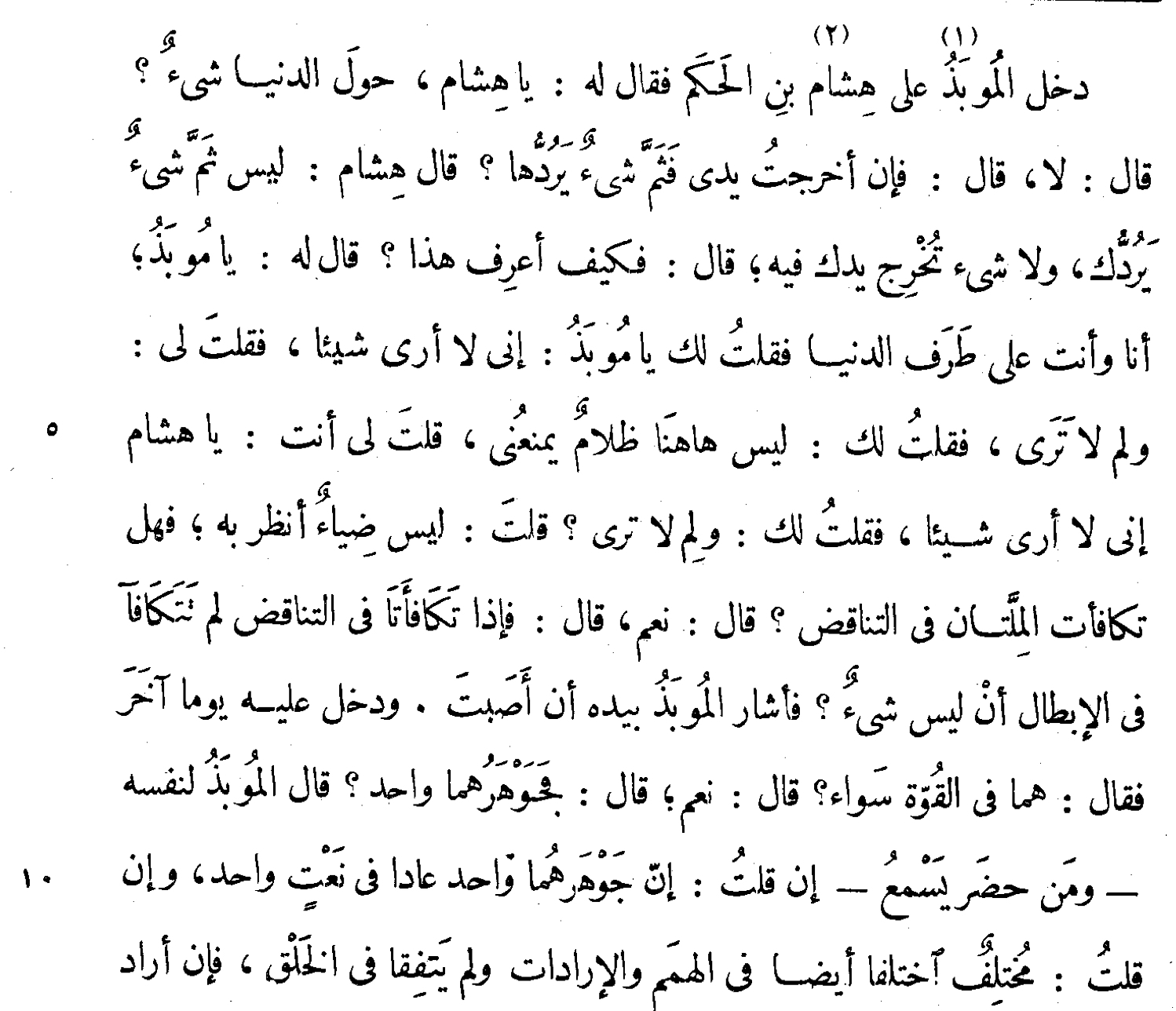

Let us consider one representative example. Ibn Quṭaybah preserves a debate in his ʿUyūn al-akhbār between Hishām and a Persian mobad, a Zoroastrian cleric of sorts.

Hishām was asked if there was anything outside the cosmos or the world, to which he replied that there is nothing beyond the end of the world. To illustrate, he told the mobad that if he imagined extending his hand beyond the edge of the cosmos, he would not be able to conceive such a scenario, since there would be nothing there.

Hishām, it seems, denied the existence of vacuums. This “hand-at-the-edge” thought experiment is not original with him, however. It traces back to the ancient Greek thinker and scientist Archytas of Tarentum, who died around 347 BCE and was a friend of Plato.

Archytas devised a similar idea, stating: “Assume that the universe is finite and I am at one border of the universe. What hinders me from stretching my hand beyond this limit? Nothing.”

Was Archytas, one wonders, Hishām’s ultimate source? It seems so—and likely transmitted through a chain of Hellenistic, late ancient, and early medieval Syriac intermediaries. Either way, future studies on the survival of Hellenistic thought in the corpus of early Islam, and especially Shiʿi literature, remain by and large uncharted territory.