How an old Yemeni legal manual helped to decipher the South Arabian script

Manuscript copies of well-known works, especially notes in them and other traces of use, can reveal surprising details. On close inspection, the Zaydi manuscript presented here turns out to be one of the oldest copies of Kitāb al-Azhār, which also has an exciting history of provenance and reception.

Yemeni-Zaydi works form one of the numerous thematic specializations in the rich Arabic manuscripts collection of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Most of them, 264 volumes, belong to the acquisitions brought back by the Bohemian-Austrian researcher Eduard Glaser (1855–1909) from his first two trips to Southern Arabia between 1884 and 1886 (Rauch 2021). Ahlwardt’s catalog made the literature of the Zaydites known to European orientalists on a larger scale for the first time. The manuscript from Southern Arabia with the longest presence in the State Library, however, had entered the library already in its founding period in the second half of the seventeenth century and originates from the collection of the German orientalist Christian Ravius (1613–77). This copy with the shelfmark Ms. or. quart. 110 contains the well-known compendium on Zaydī fiqh, Kitāb al-Azhār fī fiqh al-aʾimma al-aṭhār of Aḥmad ibn Yaḥyá ibn al-Murṭaḍá (d. 840 AH/1436) (see the blog post by Hovden and Mansoor for more information on this work).

A very old copy of Kitāb al-Azhār

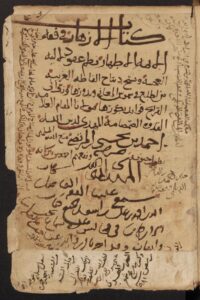

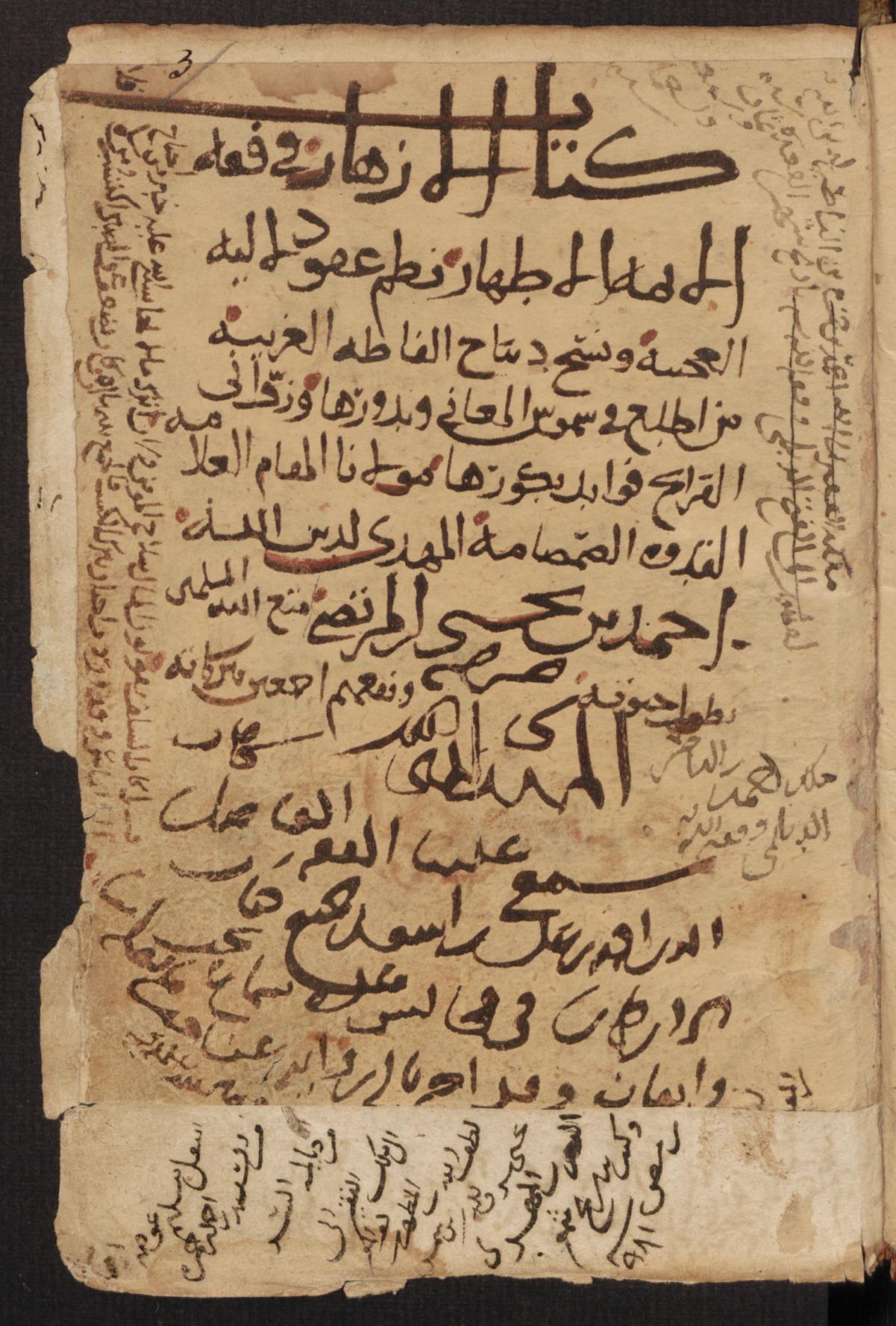

The exemplar of Kitāb al-Azhār presented here is remarkable in many respects. First, it appears to be one of the oldest known surviving copies of this widely used legal compendium, if not the oldest. The colophon provides us with the date Rajab 806 AH/1404. According to historical sources, Aḥmad ibn Yaḥyā ibn al-Murtaḍā completed this work during his stay in prison between the years 794 AH/1392 and 801 AH/1399, after his failed claim to the imamate. Ahlwardt erroneously gave the year 956 AH/1549 as the date of the copy. He was probably tempted to do so by a note that the previous owner Ravius placed next to the colophon. That both scholars misinterpreted the figure provided in the colophon of the manuscript and that it was copied already in 806 AH/1404 while the author was still alive, is strongly supported by the eulogy on the title page on fol. 3a (mattaʿa Llāh al-muslimīn bi-ṭūli ḥayātihī). Even more striking is an audition certificate given by the author to the copyist Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī ibn Asʿad ibn Fāʾid. The certificate is signed with al-Mahdī li-Dīn Allāh, the name under which Aḥmad ibn Yaḥyā claimed the imamate in the year 793 AH/1391 after the death of Imam al-Nāṣir Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn. A note testifying to the collation of the text in presence of the author (balagha qiṣāṣatan [. . .] samāʿan ʿalā al-muṣannif) in the year 838 AH/1434, that is, two years before the death of the author, can be read on the final folio (114a).

Provenance

A special characteristic of the Berlin collection is that a considerable number of the Yemeni manuscripts originate from libraries of Zaydi rulers, their family members, or scholars closely associated with them. The manuscripts often contain numerous notes that reflect the turbulent history of Northern Yemen between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. In Ms. or. quart. 110 we also find several traces of changes of ownership. According to a note on fol. 3a, the manuscript was sold to a great-grandson of its author Ibn al-Murtaḍā in 981 AH/1573–4. The new owner was Luṭfallāh ibn Muṭahhar, himself the grandson of the influential ruler Sharaf al-Dīn Yaḥyā (d. 965 AH/1557) and the father of the historian ʿĪsā ibn Luṭfallāh (d. 1048 AH/1638). After the Ottomans’ interim entry into Yemen, Luṭfallāh ibn Muṭahhar was one of the Zaydi sayyids captured by the Ottomans and brought to Istanbul, where he died in the year 1010 AH/1601–2. Probably, he had been able to take some books with him.

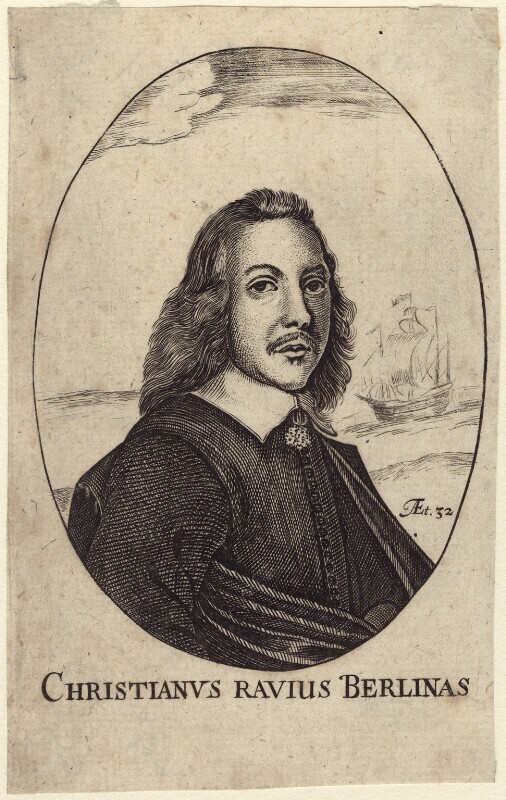

Christian Ravius (1613–1677) spent the years from 1639 to 1642 in Turkey, where he not only learned Ottoman-Turkish in a very short time but also acquired manuscripts. After his return to Europe, he taught in the Netherlands and England before he was finally appointed professor in Frankfurt an der Oder in 1772. The Berlin library acquired numerous volumes from his estate in 1691 and 1707. Ravius published a sales catalog of his manuscripts containing 380 items already in 1669, and in it he describes the Yemeni copy (number 78) as “Liber Introductorius in Jurisprudentiam Muhammedanam.”

Reception history

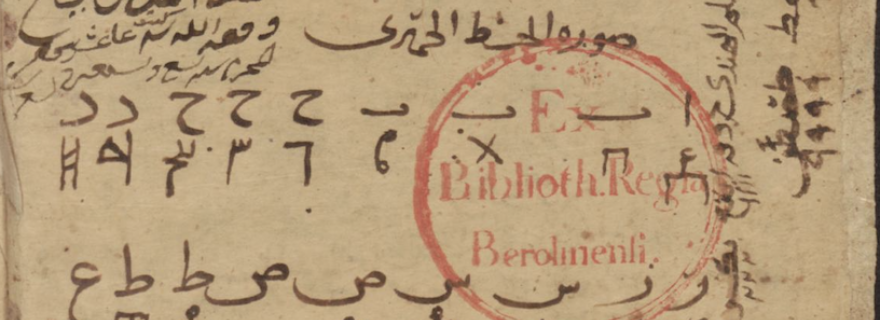

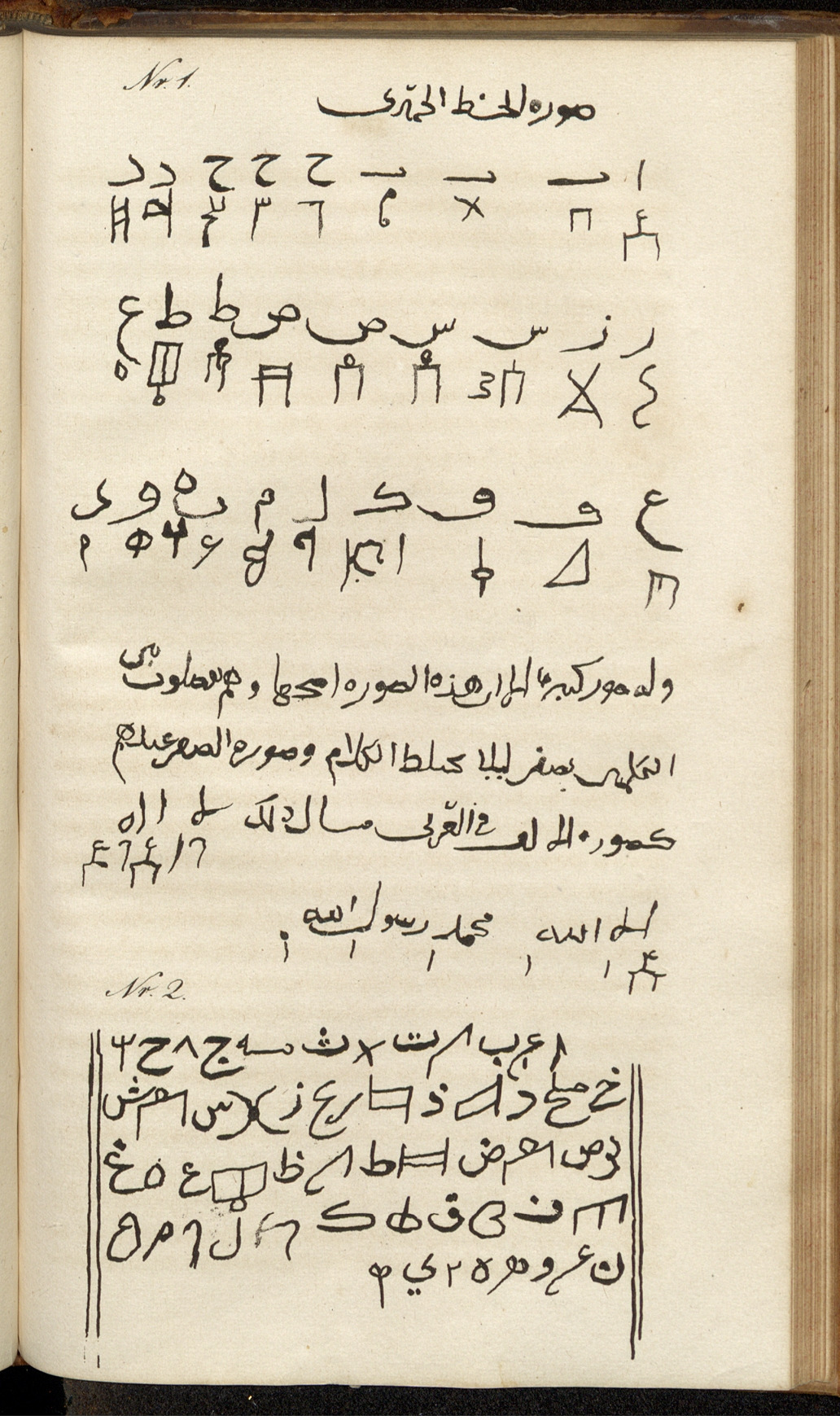

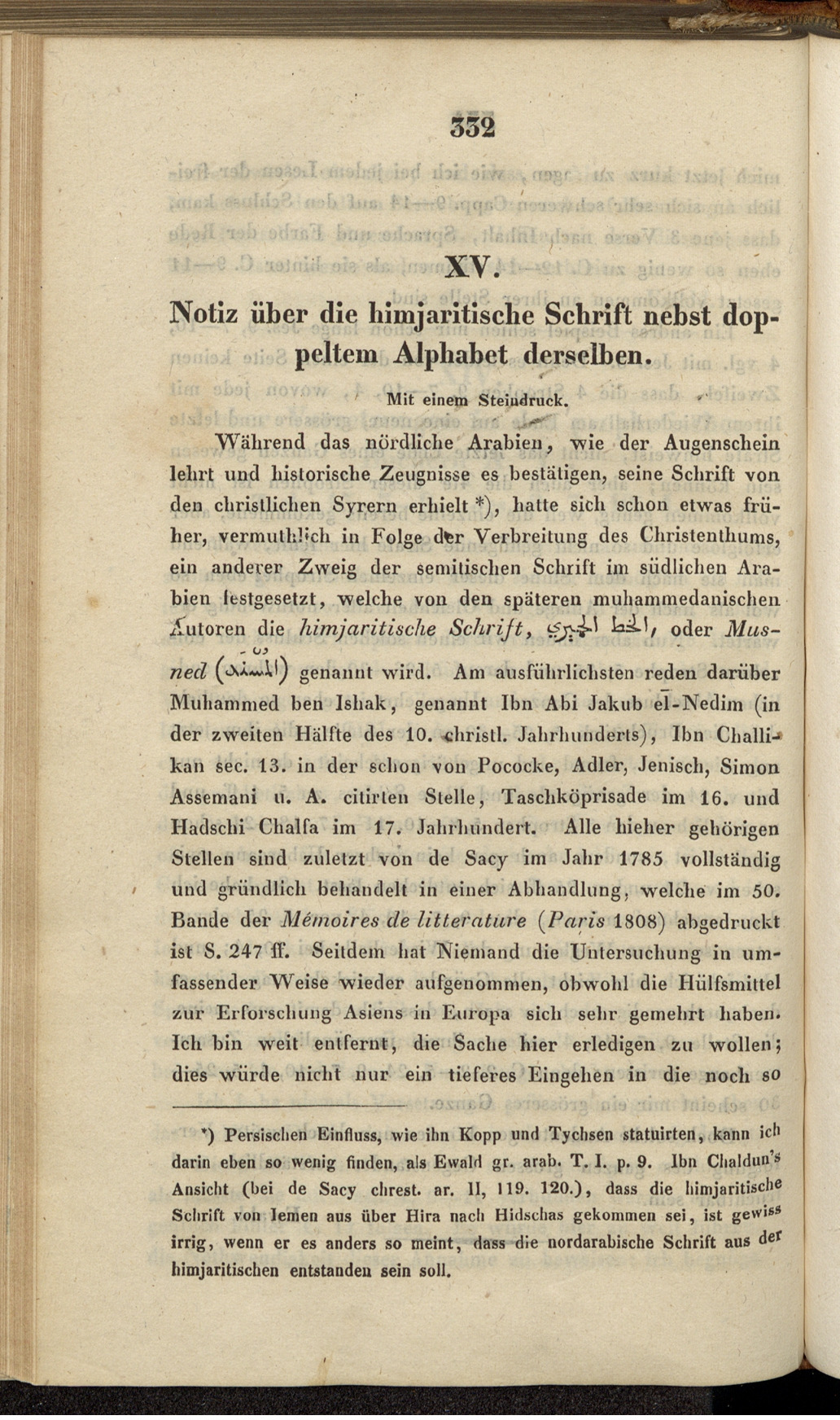

Several decades before the publication of Ahlwardt’s catalog, the manuscript had already attracted the interest of Orientalists, not so much because of its legal content, but rather because of a peculiar note on an endpaper, containing an explanation of the Himyarite alphabet. The German Orientalist Emil Rödiger (1801–74) reproduced this page as early as 1837 in an essay on the Himyarite script. In 1841, at about the same time and independently of each other, Rödiger and the eminent theologian and Semitist Wilhelm Gesenius (1786–1842) both published articles suggesting a way of deciphering the Himyarite script. Rödiger succeeded in deciphering more letters correctly than Gesenius. This may have been due to the fact that Rödiger relied on the alphabets handed down in Arabic manuscripts more than his colleague (see Stein 2013). The manuscript of Kitāb al-Azhār is thus also a witness to the fact that knowledge of ancient South Arabian cultures was never completely lost in Yemen.

References

Rödiger, Emil: „Notiz über die himjaritische Schrift nebst doppeltem Alphabet derselben.“ Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 1 (1837): 332-40.

Stein, Peter: „Wilhelm Gesenius, das Hebräische Handwörterbuch und die Erforschung des Altsüdarabischen.“ In: S. Schorch and E.-J. Waschke (eds.): Biblische Exegese und hebräische Lexikographie: Das „Hebräisch-deutsche Handwörterbuch“ von Wilhelm Gesenius als Spiegel und Quelle alttestamentlicher und hebräischer Forschung, 200 Jahre nach seiner ersten Auflage. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter 2013, 267–301.

Rauch, Christoph: „‘Im Wettkampfe mit den Bibliotheken anderer Nationen‘: Die Erwerbung arabischer Handschriften an der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin zwischen 1850 und 1900.“ In: S. Mangold-Will, C. Rauch and S. Schmitt (eds.): Sammler – Bibliothekare – Forscher: Zur Geschichte der Orientalischen Sammlungen an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Frankfurt/M.: Klostermann 2021, 87–150.

Rauch, Christoph: “Yemeni manuscripts of diverse provenance at the Berlin State Library.” In: H. Ansari and S. Schmidtke (eds.): Yemeni Manuscript Cultures in Peril. Piscataway: Gorgias Press 2022, 385–415.

This blog entry is part of the Zaydi Studies Series commissioned and edited by Ekaterina (Kate) Pukhovaia, Leiden University.