Miracles of Mary between Ethiopia and the Arabic-speaking world

How did stories about the Virgin Mary travel between the Middle East, Europe and the Horn of Africa?

A less-known translation movement

Translation of texts played an important role in the transfer of knowledge between premodern communities. The Middle East witnessed several such translation efforts in its medieval and early modern history. The great translation movement that took place in Abbasid Baghdad made numerous works of Greek philosophy and science available in Arabic. The Syriac Christian translators, who completed this task under the patronage of Muslim rulers, preserved numerous works of antique authors through this effort. This played an important role in the history of Arabic and Islamic science, as well as the history of European thought.

The Abbasid translation movement was only one of these great transfers of knowledge. An equally impressive translation effort brought texts from Arabic into Geʿez (Classical Ethiopic) over a period of several centuries. Interestingly, some of the same texts that took shape during the translation movement in Baghdad were subsequently translated into Geʿez during this period of translation, for example, the biblical commentaries of the Church of the East theologian Abū-l-Faraj ʿAbdallāh Ibn al-Ṭayyib (d. 1043). The texts that were translated in this transfer of knowledge came from Middle Eastern and Egyptian Christian communities and included a variety of texts. One of the most influential texts in the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Church was translated from Arabic into Geʿez at this time, the Miracles of Mary.

What are the Miracles of Mary?

The Miracles of Mary is a collection of stories about the life and miraculous works of the Virgin Mary. These stories can be based during the earthly life of the Virgin Mary as well as after her time on earth has ended. Many of the tales within this collection are quite old and draw upon Christian source materials such as the canonical gospels, the Infancy Gospels, including the Protoevangelium of James, and the Vision of Theophilos. The themes of the miracle stories are diverse, among the most common are healing, protection, resurrection, care and provision for children, journeys, and the monastic life.

Stories about the life and miracles of the Virgin Mary that stretch beyond what is described in the canonical gospels have long been of interest to Christian readers. By the early seventh century, collections of the miraculous deeds of the Virgin Mary were being composed and compiled. The Byzantine monk John Moschus (d. 619) wrote the Spiritual Meadow, in which he compiled several miracle stories that he collected during his travels in the Levant and Egypt.

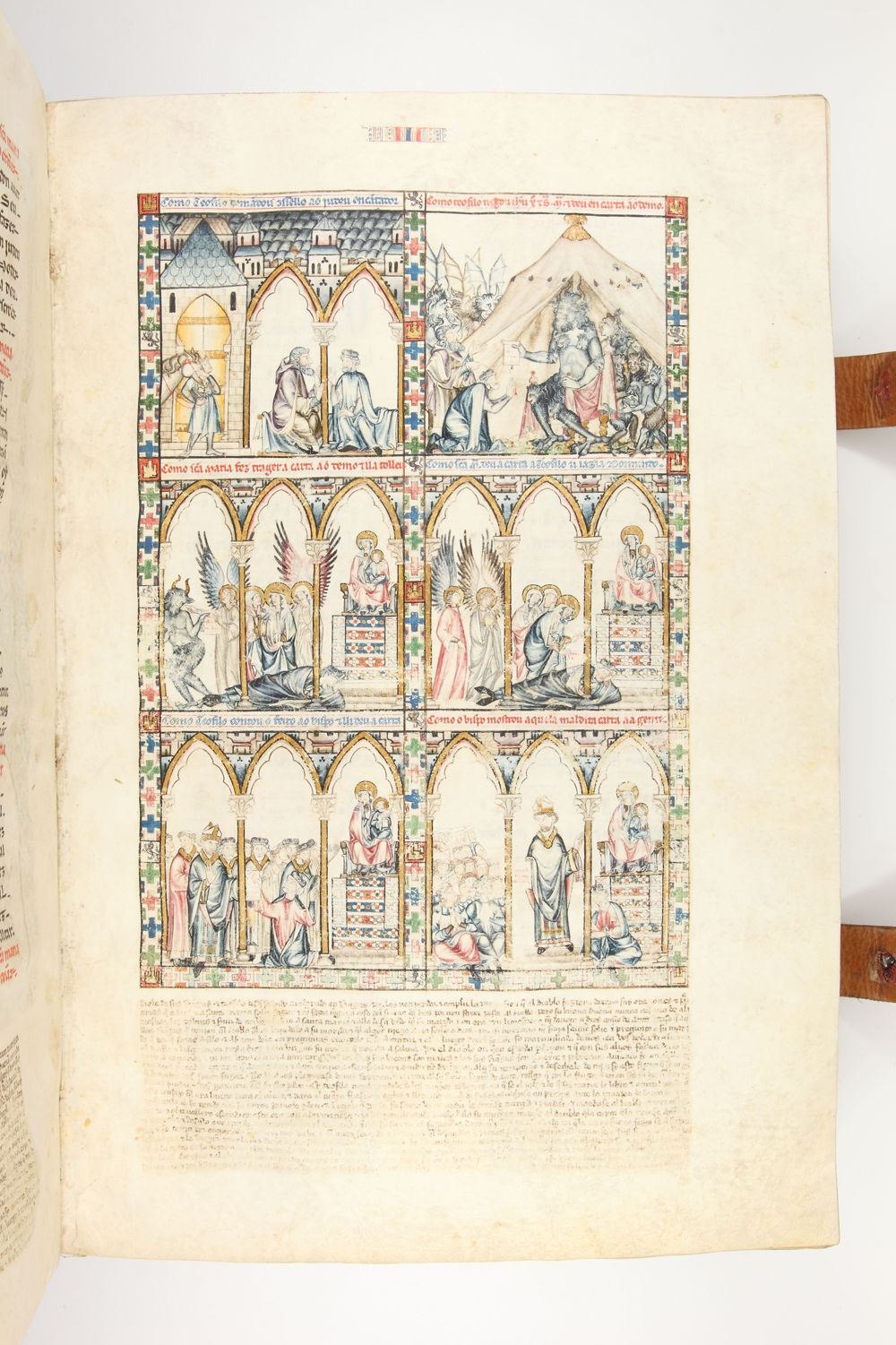

These stories made their way to the Catholic West and quickly grew in popularity. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, stories were collected into richly illuminated manuscripts copied in France, Italy, Spain, and Germany. The European stories are primarily composed in French and Latin, along with various other European vernaculars. It is during the thirteenth century that these European stories are translated into Arabic in Egypt and join an existing literary tradition about the life and works of the Virgin Mary.

Miracles of Mary in the Middle East

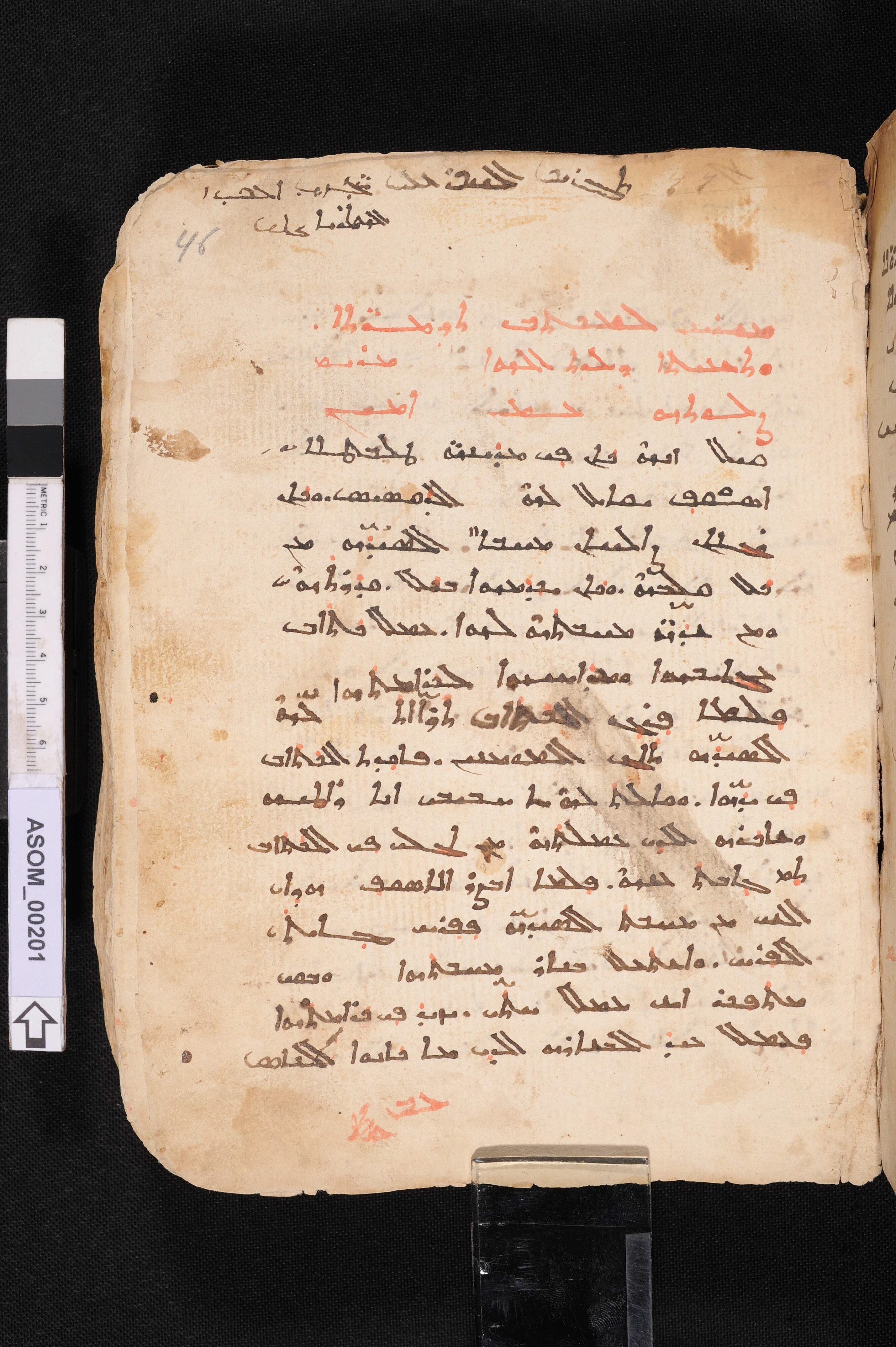

Christians of the Middle East and Egypt also composed, collected, and copied stories about the Virgin Mary. We still know little about this tradition. Up to this day, an article published in 1924 by the French scholar Louis Villecourt is the starting point for any inquiry into this topic. [L. Villecourt, "Les collections arabes des Miracles de la Sainte Vierge", Analecta Bollandiana vol. 42 (1924), pp. 21-68, 266-288]. The German Orientalist Georg Graf, in his Geschichte der Christlichen Arabischen Literatur, cataloged the Arabic-language stories (including in Garshuni) and discussed the connection between the Syriac and Arabic versions, as well as the transmission of these texts to Ethiopia.

The Arabic-language Miracles of Mary exist in two collections that have separate transmission histories. The earlier collection includes 74-75 stories and has no author attribution and was translated into Arabic from European languages, likely Latin and French. The oldest known copy of this collection – Paris 177 – dates to 1289 AD. The later collection containing 68 stories was put together in Greek by Agapios (Athanse Landos) at the turn of the seventeenth century and was then translated into Arabic by Macarius, the Patriarch of Antioch. Both collections predominantly contain stories that originate in Europe, Byzantium, and the Levant in the Middle Ages.

However, the Miracles of Mary in the Arabic-speaking world were not limited to these two collections. In fact, one of the most circulated stories related to the Virgin was the story of the Holy Family’s Flight to Egypt. It was part of the Copto-Arabic Synaxarium, a collection of hagiographies read annually in the Coptic Church. Another genre of texts that often refers to the Virgin was maymar (pl. mayāmir), or homily. Finally, some stories mentioning Mary were related in works with a more historical approach, like the History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria. All in all, the stories of Mary circulated in different Christian communities across the Middle East, both in Arabic and in Syro-Arabic Garshuni script from the Syriac Christian communities of the Levant and Iraq.

Many of the Marian stories originating in the Coptic Church of Egypt paid special attention to connecting Mary with the land. Coptic churches and monasteries were important centers for the production and transmission of Marian stories. Many Coptic sites emphasized their history with the Virgin, either in connection to the flight of the Holy Family to Egypt or to legends of Mary’s miraculous involvement in the founding and existence of these sites. Among such locations was Dayr al-Muḥarraq, the Monastery of the Holy Virgin in Qusqam, in Middle Egypt. According to the foundation legend of the monastery, it stands in a location where the Holy Family resided for several months during their travels. Similarly, Musturud (also known as al-Mahammah) is the location of a church dedicated to one of the stops on the Holy Family’s flight. In addition, Dayr al-Maghtis (Debra Metmaq) was known for regular appearances of the Virgin Mary and was a popular pilgrimage location.

This connection between the Coptic Church and Mary is especially relevant to the history of the textual transmission of Miracles of Mary from the Arabic-speaking world to Ethiopia. Historically, the bishops of the Church of Ethiopia were appointed by the patriarchs of Alexandria. Not only people, but also manuscripts traveled between the two regions. Unsurprisingly, the earliest Miracles of Mary stories preserved in the Ethiopic tradition predominantly entered it through the Egyptian tradition. These stories were translations from the oldest Arabic collection as well as other collections of miracles mentioning St. Mary. Interestingly, the Agapios collection was never translated from Arabic into Geʿez. Sometimes an exact Arabic Vorlage cannot be identified. Nevertheless, the study of the Ethiopian collections of Miracles of Mary allows us to identify an additional stratum of stories that originate in the Egyptian context, oftentimes in the Fatimid period (10th - 12th centuries).

The Miracles of Mary in Ethiopia and the Princeton Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Egyptian Miracles of Mary (PEMM) digital humanities project

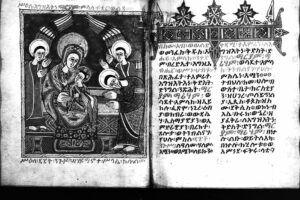

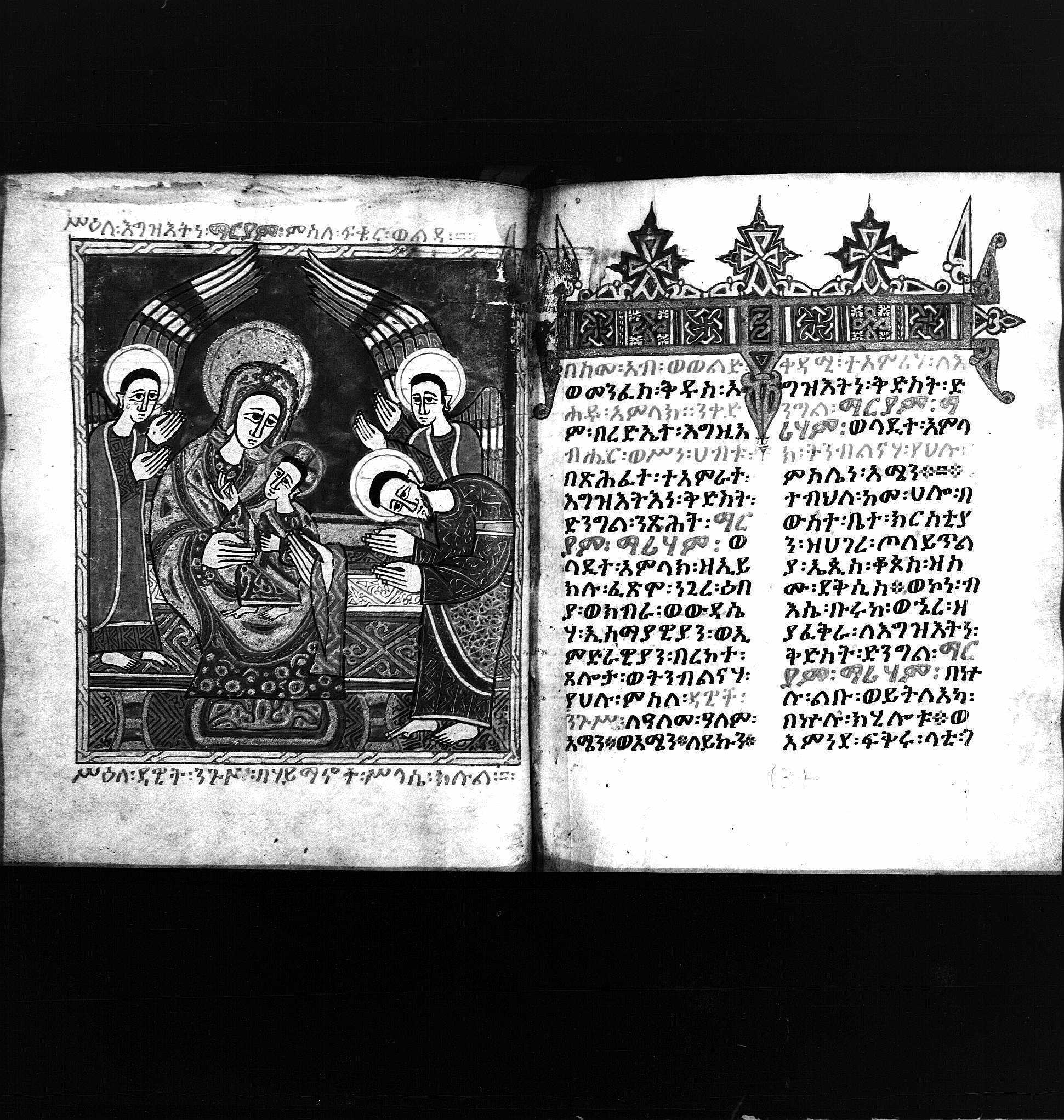

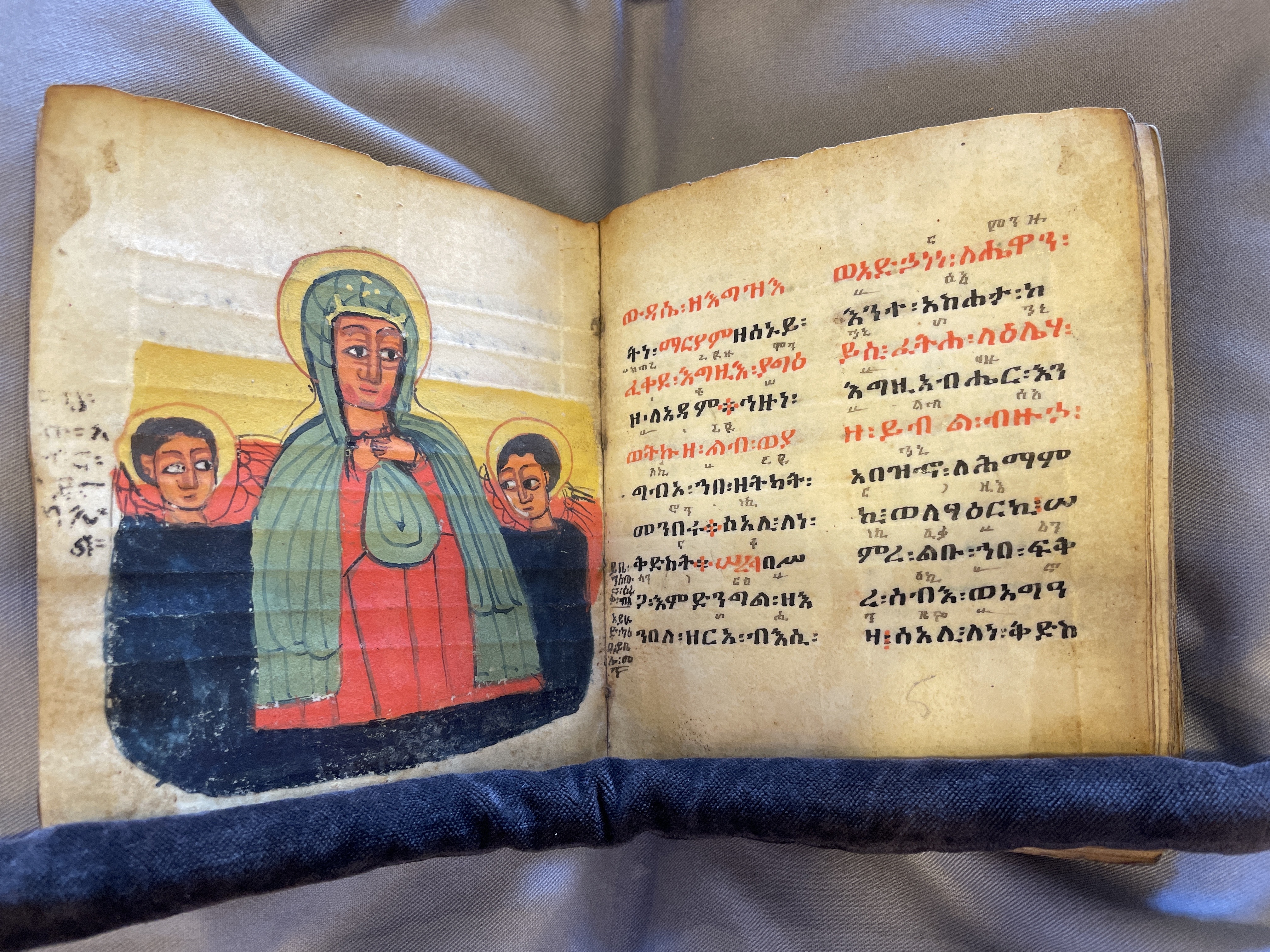

The Miracles of Mary entered into Ethiopia via the translation movement of the 14th and 15th centuries described above in which a large number of Christian texts were translated from Arabic into Gəˁəz. An initial small corpus of eight miracles was the initial translation of the Miracles of Mary into Ethiopic. Soon after, the largest Arabic corpus of 75 miracles was translated into Gəˁəz, with the exception of the final two miracle stories which are, as of yet, unattested in Ethiopic. At least fifty-eight of these stories had been translated from Latin into Arabic prior to their translation into Gəˁəz. The earliest extant copy of this corpus of seventy-five miracles in Gəˁəz was microfilmed as a part of the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML) with the shelfmark EMML 9002. This manuscript was copied in the royal scriptorium of Emperor Dawit II (r. 1379/80-1413) and features several illuminations with the king himself at Mary’s feet.

These stories translated from Arabic into Gəˁəz served as the foundation for a quickly expanding library of miracles centered upon the Virgin Mary. Emperor Zär’a Ya‘əqob (r. 1434-1468) initiated religious reforms that emphasized the centrality of the Virgin Mary within the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. One outcome of these reforms is that the Miracles of Mary became an element of the Sunday liturgy and of the large number of feasts in honor of the Virgin Mary. This emphasis and the need for miracle stories to read during these church services saw the corpus of 75 stories quickly expand to over 350 stories by the end of the reign of Emperor Ləbnä Dəngəl (r. 1508-1540). The sources for these new stories are several: 1. Adaptations of existing works on the Virgin Mary, such as the Vision of Theophilus and the Protoevangelium of James; 2. Stories newly translated from Arabic into Gəˁəz, oftentimes adaptations from historic, hagiographic, or monastic collections such as the Synaxarium or the History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria; 3. Original compositions in Gəˁəz.

The Princeton Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Egyptian Miracles of Mary (PEMM) digital humanities project, directed by Wendy Laura Belcher, is currently collecting data and analyzing the textual tradition and transmission of the Miracles of Mary in Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Egypt. The Gəˁəz language cataloging team, made up of Jeremy R. Brown, Mehari Worku, and Dawit Muluneh, have completed the cataloging of 641 manuscripts and have identified hundreds of new Marian stories. In addition, the PEMM project has already translated dozens of these Marian stories into English, this is the first translation into a Western language for many of these stories and will undoubtedly expand the readership for many of these fascinating tales.

Among the manuscripts studied in the project are five copies of the Ethiopian Miracles of Mary held at Leiden University Library. These manuscripts were copied between the eighteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century on parchment in Gəˁəz. The PEMM project for the first time catalogued and identified all the stories in these manuscripts. Leiden Or. 12833 is a particularly interesting illuminated manuscript that weaves together the miracle story about the Syrian potter who writes the popular hymn the Praises of Mary (ውዳሴ፡ ማርያም፡ Wəddase Maryam) along with the hymn itself. The Ethiopian Miracles of Mary manuscripts are but a small portion of the Ethiopian collection at the Leiden University Library. There exists an inventory (Catalogus van de Ethiopische Handscriften, Rachel Struyk) of the collection, as well as an unpublished catalogue of some of the materials (preserved in cod. Or. 23.405) by Dr. Sergew Hable Selassie, director of the Ethiopian Manuscripts Microfilm Library. Nevertheless, the more than 250 Ethiopian manuscripts in the Leiden University Library are still awaiting a detailed study.