Philistine Mutakallimīn

The earlier Islamic theologians had an argument for God’s existence that traded on the (it wouldn't be inaccurate to say) ‘arbitrary limits’ in things - the basic idea being that, though things are a certain definite way, they could have been otherwise e.g., the earth’s diameter is 7918 miles, but it could’ve been more (say 8000), or less (say 6459). So it’s arbitrary that it is one determinate way and not any other. And the arbitrariness, they want to show, is ultimately rooted in the divine will.

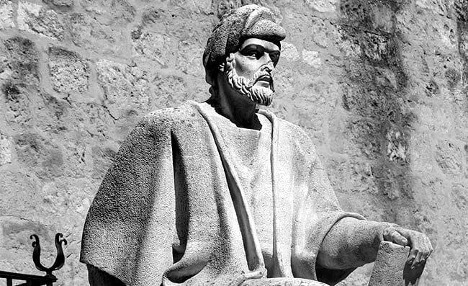

The Islamic philosopher Ibn Rushd (Averroes) found that thought extremely problematic, criticizing it and the argument they based on it. The critique appears in his Kashf ‘an manahij al-adilla, where he parses the reasoning of the Ashʿarī theologian Juwaynī in particular.

Let us first state the argument Juwayni offers, then consider the issues Ibn Rushd raises for it.

The argument

The thinking the Commentator targets proceeds as follows:

- Things in the world could have been otherwise (e.g., different in size, shape, motion, number, direction, etc.)

- Whatever could have been otherwise requires an agent to specify it in one way rather than another.

- Therefore, the world must have a specifier or designer (i.e., God) who chose one configuration among many possible alternatives.

The critique

Ibn Rushd pushes back against both the coherence and implications of this argument. His critique, directed at the minor premise, proceeds in several steps. He labels it “rhetorical” and says it only appears persuasive at a surface level. But on reflection, it’s either clearly false, because it assumes contingency where there may, in fact, be necessity, or it’s unclear at best, since the modal status may be unknown because the causes at work remained unknown.

As for its obvious falsehood in some cases, e.g., the human being could not exist with a totally different nature. For our form is not arbitrarily assigned. As for the other cases, e.g., eastward or westward planetary movement, they may seem arbitrary but could in fact be grounded in causes not readily known to us and so be necessary. The inference of contingency from conceivability is misleading and rash.

Ibn Rushd draws a perceptive an analogy with artisanship in motivating the critique:

Consider some artifact, say a clock. An uncultivated person, looking at it, may think the components of such an artifact could have been otherwise. To him, it seems arbitrary that it has a rubber gasket at all or a hex nut of a certain shape, etc. But the skilled artisan that made it knows that every part is ordered toward a purpose and is the way it is for a definite reason. And even if some part may not be necessary, it still useful in that it contributes, in accordance with the artisan's wisdom-judgment, to the larger excellence or perfection of the whole of which it is a part. Similarly, Ibn Rushd notes, the universe reflects divine ḥikma (wisdom): so, its order is not arbitrary but necessary in some parts, useful in others, and fully purposeful. Thus, he concludes, assuming, à la the amateurs that are the theologians, a purely arbitrary configuration gainsays the idea that the world is the product of divine art and divine artisan (al-sani’).

So the irony, which Ibn Rushd thinks is lost on the theologians, is that their reasoning, though aimed at proving God’s existence, ends up nullifying the divine wisdom they intend to uphold. For if all features of the world could have been otherwise, and there are no necessary causes grounding them, then there's no objective reason to say some particular configuration is better or wiser than any other. A consequence of this is that the world begins to resemble a random or whimsical arrangement, rather than a rationally ordered whole. Consequently, no real or objective ḥikma can be discovered in creation and so be ascribed to God’s creative activity. Ibn Rushd says this would be akin to a designer whose products are not governed by cause or reason based artisanship; it strips creation of its intelligibility and makes divine wisdom inscrutable. With that, we’re led, he warns, to a dangerous theological consequence: a denial of ḥikma as a divine attribute. For if everything could have been otherwise for no objective reason - e.g., we could’ve just as equally seen through our toes as we in fact do by our eyes because nothing about the latter requires that seeing be by them - then calling God wise becomes meaningless. In reality, God would be no more than a chooser between equally arbitrary options.

Ibn Rushd’s criticisms here should be seen as advocating for a teleological and essentialist view of nature. According to that view, i) things have natures and purposes, ii) these are grounded in intelligible, knowable causes, and iii) the world is rationally ordered, where this order reflects God’s wisdom. In this way, the critique echoes Peripatetic metaphysical principles on which necessity in nature is not just logical but is also teleological. By contrast, the theologians’ argument has a voluntarist and occasionalist impetus to it i.e., insofar as it imagines the world as purely contingent in every aspect and governed by sheer divine will.

The Averroean critique of this instance of kalām thinking, then, has both an epistemological and theological component. With regards to the former, it warns against taking imaginings and ignorance of causes or reasons as proof of contingency. With regard to the second, it maintains that to say “everything could be otherwise” is not really a religion-friendly thesis (which is their usual motivation); for it in fact undermines divine wisdom. In contrast, he defends the necessary and teleological order of the cosmos, not arbitrary configurational limits or hypothetical opposites, as the proper basis for affirming God’s existence and attributes.

The text from Kashf ‘an manahij al-adilla fi ‘aqa’id al-milla runs as follows:

As for the second path [for establishing God’s existence], it is that which Abu Ma’ali [Juwayni] devised in his treatise known as the Nizamiyya. He based it on two premises.

The first of the two is that ‘the world, and everything in it, may be opposite from the way it actually is’, so that it is possible that e.g., it be smaller than it is, or bigger than it is, or be shaped differently from the way it is [now] shaped, or the number of its bodies may be other than the number they [now] are, or that the motion of every moveable in it be in a direction contrary to the direction it [now] moves, such that it is possible that a stone undergo motion upwards, and fire downwards, and the [planetary] eastern motion be western, and the western be eastern.

The second premise is that ‘what is possible begins to exist (muhdath) and it has a cause’ i.e., an agent that makes one of the two possible alternatives more worthy for it than the other.

As for the first premise, it is rhetorical and [only] prima facie the case. With regards to some parts of the world, its falsity is self-evident – for example, a human existing upon a nature different from this nature he has. And with regards to other parts [of the world], the matter is doubtful – for example, the eastern motion’s being western and the western one eastern, since that’s not known per se; for it’s possible that for [its impossibility] there’s a cause whose existence is not evident in itself, or that [its cause] is among the causes hidden to human beings.

It seems that what occurs to a human being at first when reflecting on these things is similar to what occurs to someone who reflects on the parts of artifacts without being from the people of those arts. That is because for someone in this situation it prematurely occurs to his mind that everything in those artifacts or most of them can possibly be contrary to the way they [actually] are, and that there can come to exist from this artifact that act itself for the sake of which it wasn’t made i.e., its end. Consequently, in that artifact, upon this [act], there wouldn’t be a place for wisdom.

As for the designer, and whoever shares with the designer in something of the knowledge pertaining to the art, he sees that the matter is the contrary of [the prima facie view]. [He sees] that there’s nothing in the artifact except what is requisite and necessary, or [something] so that by it the artifact is more perfect and excellent, even if not necessary for it. This is the meaning of art and it is evident that created things are similar in this meaning to artifacts. So praise be to the Creator the All-knowing!

Thus, this [first] premise, qua being rhetorical, is perhaps suitable for the persuasion of everyone, but qua being false and invalidating of the wisdom of the Designer, it is not appropriate for them. And it only becomes annulling of wisdom because wisdom is nothing more than knowledge of the causes of something. And if something has no necessary causes that require its being in accordance with the description by which it is an instance of that species, then there’s no knowledge here that the All-wise Creator made proper to it and not to something else. Just as were there no necessary causes of the being of artifacts here, there wouldn’t be any art here at all, nor a wisdom that’s ascribable to the designer as opposed to one who isn’t a designer. And what wisdom would there be in the human being if all his activities and operations can possibly arise from whatever organ or from no organ – so that vision, for example, comes about by the ear just as it does by the eye, or smelling by the eye just as it is carried out by the nose? All this is a nullification of wisdom and of the meaning by which He calls Himself wise – exalted and sanctified be His names above that!

Arguably, contemporary talk in science about ‘fine tuning’ (for life on our planet) and ‘gravitational constants’ (for the order in solar systems) bears out Ibn Rushd’s claims. To the superficial observer, such facts about the world might appear contingent, even chancy; but on reflection, a kind of necessity is involved. For the fact that say a small change to the strong force results in stellar or chemical breakdowns is clear evidence against arbitrary configuration. Thus, we can imagine Ibn Rushd, briefed on current, relevant empirical data, saying something like the following to the theologians: ‘the actual value of the strong force (and not just any old value) is required for the stable, intelligible, purposive order of the universe - an order in which e.g., stars can form, burn hydrogen, and synthesize heavier elements, allowing for the emergence of life. If it could not be otherwise without destroying the harmonious structure of nature, then it is as it must be. Divine wisdom is found precisely in this necessity and not in some arbitrary divine choice.’

There’s a broader lesson here to learn here though. For Ibn Rushd’s critique does more than merely expose a weakness in a particular kalām proof; it exemplifies a deeper intellectual virtue that he thought essential to the life of the mind. By refusing to accept appearances and demanding clarity about causes/reasons, Ibn Rushd is promoting a mode of inquiry about phenomena that respects the rigor of logic. His engagement with the mutakallimīn is then a lesson in critical thinking - training the reader to distinguish rhetorical persuasion from genuine demonstration, to resist conflating ignorance with possibility, and to test theological doctrines against the standards of intelligibility and coherence. In this way, the Averroean analysis fosters precisely the sort of theoretical investigation and productive debate that he believed would elevate and advance theological study - moving it toward greater precision, deeper understanding, and a more faithful representation of divine wisdom.